Why ghosts wear clothes or white sheets instead of appearing in the nude

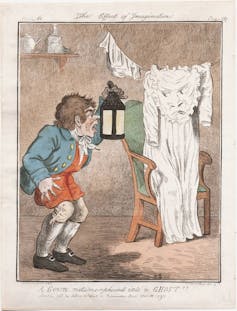

When you think of a ghost, what comes to mind? A ghastly, mouldy winding-sheet? A malevolent pile of supernatural armour? Or a sinister gentleman in a stiff Victorian suit?

In 1863 George Cruikshank, the caricaturist and illustrator of Dickens’s novels, announced a “discovery” concerning the varied appearance of ghosts. It does not seem, he wrote:

That any one has ever thought of the gross absurdity and impossibility of there being such things as ghosts of wearing apparel … Ghosts cannot, must not, dare not, for decency’s sake, appear without clothes; and as there can be no such thing as ghosts or spirits of clothes, why then, it appears that ghosts never did appear and never can appear.

Why aren’t ghosts naked? This was a key philosophical question for Cruikshank and many others in Victorian Britain. Indeed, stories of naked or clothesless ghosts, especially outside folklore, are exceedingly rare. Sceptics and ghost-seers alike have delighted in thinking about how exactly ghosts could have form and force in the material world. Just what kind of stuff could they be made of that allows them to share our plane of existence, in all its mundanity?

The image of the ghost as a figure in a white winding-sheet or burial shroud has retained its iconic status for hundreds of years because it suggests a continuity between the corpse and the spirit.

The main social role of the ghost before the modern period was to carry a message to the living from beyond the grave, so the link to burial clothing makes sense. This can be seen in the medieval trope of the Three Living and the Three Dead, whereby some hunters encounter their future skeletal corpses, wrapped in linen, admonishing them to remember death.

Yet by the mid-19th century, with spiritualism and early forms of psychical research spreading across the western world, people began to report seeing ghosts dressed in everyday and contemporaneous clothing.

This raised problems for those interested in investigating the reality of ghosts. If the ghost was an objective reality, why should it be wearing clothes? If the tenets of spiritualism were true, should the soul which has returned to visit the earth not be formed of light or some other form of ethereal substance? Were the clothes of spirits also spiritual, and if so, did they share in their essence or were they the ghosts of clothes in their own right?

You could adopt an idealist position and say that the clothes were metaphysical ideas bound up with the immortal identity of the wearer – the identity of the ghost meaning something more than simply the apparition of a soul-force.

Another explanation was that ghost-seers dress the ghost, automatically, through unconscious processes. And so we see a ghost in its usual dress because that is the mental picture we have of the person, and this choice of garment is most likely to inspire recognition.

The critic and anthropologist Andrew Lang drew comparisons between dreaming and ghost-seeing in 1897 when he stated that:

We do not see people naked, as a rule, in our dreams; and hallucinations, being waking dreams, conform to the same rule. If a ghost opens a door or lifts a curtain in our sight, that, too, is only part of the illusion. The door did not open; the curtain was not lifted … It was produced in the same way as when a hypnotised patient is told that “his hand is burned”, his fancy then begets real blisters.

For Lang, the clothes of ghosts were the stuff that dreams are made of. The implication of this, that ghost-seers are dressers, but not undressers, seems to reflect a pervading morality of ghosts, whereby most 19th-century spirits were sanitised and chaste. Lang’s odd assumption that there was no nakedness in dreams echoes this.

The matter of spirits

Fashion and clothing were central to the identification of class, gender and occupation in the Victorian period. The ghosts of the servant class seemed to be especially tied to their clothes, rather than their faces or voices – a theme that comes out in some ghost reports submitted to The Strand magazine in 1908.

Here, a ghost-seer reported seeing “a figure, which had nothing supernatural about it, being simply that of a servant in a light cotton dress … and with a white cap on … The whole figure had the general appearance of the housemaid, so that she had been the one I had thought of. It was not in the least like the cook, who dressed in much darker cottons”.

Clothes identify people and make them capable of representation – nakedness disrupts this means of instantly categorising someone.

The issue of ghost clothes is interesting for historians of the supernatural because, like a loose thread, pulling at it starts to unravel some of the assumptions about matter in spiritualism. Do ghosts retain the injuries or disabilities that befell them in life? And what about the erotic fleshiness of spirits – the touching and kissing between the living and the dead in the séance room and the “ectoplasm” (a gauze-like spiritual substance) photographed emerging from the orifices of mediums? Could the living even have sexual intercourse with ghosts?

These kinds of knotty debates have not disappeared in the 21st century. Indeed, “spectrophilia” – or the love of ghosts – is a fetish that is a lively topic of debate on the internet today. Another turn of the screw in the long history of how spirits matter in the world of the living.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.![]()

Shane McCorristine, Reader in Cultural History, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.