The year is 19 AD. The Roman Empire is in turmoil. The emperor Tiberius is old and sick, and the succession is uncertain. In this time of chaos, one man stands out as a beacon of hope: Germanicus, the nephew and adopted son of Emperor Tiberius.

Germanicus is a popular and charismatic figure. He is a brilliant general and a skilled diplomat. He is also a devoted husband and father. But Germanicus is also a threat to Tiberius' power. The emperor fears that Germanicus will one day usurp the throne.

In 19 AD, Germanicus is sent to the East to quell a rebellion. But while he is there, he falls ill and dies. The official cause of death is fever, but many people believe that Germanicus was poisoned via witchcraft.

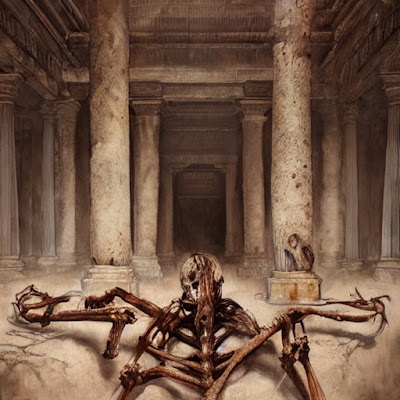

Proofs also of fascination and sorcery were pretended to be found, such as the ashes and bones of human bodies, dug up again half burnt and stained with black blood, magic forms of devoting persons to the infernal gods, and Germanicus's name graved on sheets of lead.

...a slave reported with a face of terror that as he had been washing the floor in the hall he had noticed a loose tile and, lifting it up, had found underneath what appeared to be the naked and decaying corpse of a baby, the belly painted red and horns tied to the forehead. An immediate search was made in every room and a dozen equally gruesome finds were made under the tiles or in niches scooped in the walls behind hangings. They included the corpse of a cat with rudimentary wings growing from its back, and the head of a negro with a child's hand protruding from its mouth. [...] Cock's feathers smeared in blood were found among the cushions and unlucky signs were scrawled on the walls in charcoal, sometimes low down, as if a dwarf had written them, sometimes high up, as if written by a giant -- a man hanging, the word Rome upside down, a weasel; and, though only Agrippina knew of his private superstition about the number seventeen, this number was constant recurring. Then appeared the name Germanicus, upside down, every day shortened by a letter. [...] He died on the ninth of October, the day that the single G appeared on the wall of his room facing his bed, and on the seventeenth day of his illness.

Of course, all modern scholars deny that witchcraft could have been the cause of Germanicus's death, since witchcraft is not acknowledged as real. Poisoning is more commonly attributed in modern sources. But, as the medieval Suda explains, there were believed to be three kinds of occult practice: goetia, magia and pharmacia. In this sense, pharmacia (sometimes translated as witchcraft) was virtually synonymous with poisoning. "But [the word] witchcraft [is used] when some death-dealing concoction is given as a potion by mouth to someone."

In this sense, pharmacia was virtually synonymous with modern black magic. After all, what is black magic if not the use of natural means, rather than weapons, to kill someone?

So when Germanicus died, everyone knew that he had been poisoned. They knew that it was pharmacia, or witchcraft. And they knew who had done it.

It was Piso.

Piso was the governor of Syria, and he was a jealous man. He was jealous of Germanicus's popularity, and he was jealous of his success. So he poisoned Germanicus.

But Germanicus knew what had happened. He knew that Piso had poisoned him. And he made sure that everyone else knew it too.

Before he died, Germanicus made his wife, Agrippina, swear to avenge his death. And she did. A public trial was held, and Tiberius made allowances for Piso to summon witnesses of all social orders, including slaves, and he was given more time to plea than the prosecution, but it made no difference: before the sentencing, Piso had died. He committed suicide, though Tacitus supposes that Tiberius may have had him murdered, fearing his own implication in Germanicus' death.

And that's the story of how Germanicus was poisoned by witchcraft.