I've been amusing myself with terrifying old murder ballads. Here's one from Francis James Child's collection that should be turned into a Hollywood film any day now.

93F.1 SAID my lord to his ladye, as he mounted his horse, (bis) Take care of Long Lankyn, who lies in the moss. (bis) 93F.2 Said my lord to his ladye, as he rode away, Take care of Long Lankyn, who lies in the clay. 93F.3 Let the doors be all bolted, and the windows all pinned, And leave not a hole for a mouse to creep in. 93F.4 Then he kissed his fair ladye, and he rode away; He must be in London before break of day. 93F.5 The doors were all bolted, and the windows were pinned, All but one little window, where Long Lankyn crept in. 93F.6 ‘Where is the lord of this house?’ said Long Lankyn: ‘He is gone to fair London,’ said the false nurse to him. 93F.7 ‘Where is the ladye of this house?’ said Long Lankyn: ‘She’s asleep in her chamber,’ said the false nurse to him. 93F.8 ‘Where is the heir of this house?’ said Long Lankyn: ‘He’s asleep in his cradle,’ said the false nurse to him. * * * * * 93F.9 ‘We’ll prick him, and prick him, all over with a pin, And that will make your ladye to come down to him.’ 93F.10 So she pricked him and pricked, all over with a pin, And the nurse held a basin for the blood to run in. 93F.11 ‘Oh nurse, how you sleep! Oh nurse, how you snore! And you leave my little son Johnstone to cry and to roar.’ 93F.12 ‘I’ve tried him with suck, and I’ve tried him with pap; So come down, my fair ladye, and nurse him in your lap.’ 93F.13 ‘Oh nurse, how you sleep! Oh nurse, how you snore! And you leave my little son Johnstone to cry and to roar.’ 93F.14 ‘I’ve tried him with apples, I’ve tried him with pears; So come down, my fair ladye, and rock him in your chair.’ 93F.15 ‘How can I come down, ’tis so late in the night, When there’s no candle burning, nor fire to give light?’ 93F.16 ‘You have three silver mantles as bright as the sun; So come down, my fair ladye, by the light of one.’ [The lady she cam downthe stair trip for trap; Who so ready as Bold Lambkin to meet her in the dark? 93E.18 ‘Gude morrow, gude morrow,’ said Bold Lambkin then; ‘Gude morrow, gude morrow,’ said the lady to him. 93E.19 ‘O where is Lord Montgomery? or where is he gone?’ ‘O he is up to England, to wait on the king.’ 93E.20 ‘O where are your servants? or where are they gone?’ ‘They are all up to England, to wait upon him.]93F.17 ‘Oh spare me, Long Lankyn, oh spare me till twelve o’clock, You shall have as much gold as you can carry on your back.’ 93F.18 ‘If I had as much gold as would build me a tower,’ [‘I’ll give you as much gold, Lambkin,as you’ll put in a peck, If you’ll spare my life till my lord comes back.’ 93E.22 ‘Tho you would [give] me as much as I could put in a sack, I would not spare thy life till thy lord comes back.’]93F.19 ‘Oh spare me, Long Lankyn, oh spare me one hour, You shall have my daughter Betsy, she is a sweet flower.’ 93F.20 ‘Where is your daughter Betsy? she may do some good; She can hold the silver basin, to catch your heart’s blood.’ [‘To hold my lady’s heart’s bloodwould make my heart full woe; O rather kill me, Lankyn, and let my lady go.’]93F.21 Lady Betsy was sitting in her window so high, And she saw her father, as he was riding by. 93F.22 ‘Oh father, oh father, don’t lay the blame on me; ’Twas the false nurse and Long Lankyn that killed your ladye.’ 3L.7 [There was blood in the chamber,and blood in the hall, And blood in his ladie’s room, which he liked worst of all.]93F.23 Then Long Lankyn was hanged on a gallows so high, And the false nurse was burnt in a fire just by.

You can read more versions of Lamkin here, or listen to it performed in this creepy earworm.

Bold Lankin becomes "Bo Lankins" and "false nurse" becomes "Faultress" in this. Such mishearings are typical of folk song evolution passed through oral tradition/performance rather than written.

My most exciting research turned up the oldest known print version, from 1770s Scotland as "Lammikin" -- written in a nice old style Scots dialect, and said to be sung "to the tune of Gil Morrice."

And it's there the version ends, without saying what exactly Lammikin does to the Lord's wife after luring her downstairs. A longer version of what seems otherwise to be the same song can be found.A better mason than Lammikin

Never builded wi the stane:

Quha builded Lord Weires castell,

Bot wages nevir gat nane.

"Sen ȝe winnae gie me my guerdon, Lord,Sen ȝe winnae gie me my hire,Yon proud castle, sae stately built,I sall gar rock wi the fyre.Sen ȝe winnae gie me my wages, Lord,Ȝe sall hae cause to rue."And syne he brewed a black revenge,And syne he vowed a vow."Now byde at hame, my luve, my life,I warde ȝe byde at hame:O gang nae to this day's hunting,To leave me a my lane!Of red, red blude was fu.Gin ye gang to this black hunting,I sall hae cause to rue.""Quha looks to dreams, my winsome dame?Ȝe hae nae cause to feare."And syne he's kist her comely cheek,And syne the starting teare.And syne he's gane to the good greene wode,And she to her painted bowir;Of castle, ha, and towir.They steeked doors, they steeked yates,Close to the cheek and chin:They steeked them a but a little wicket,And Lammikin crap in."Now quhere's the Lady of this castle,Nurse tell to Lammikin.""She's sewing up intill her bowir,"The fals Nourice she sung.Lammikin nipped the bonny babe,Quhile loud fals Nourice sings:Lammikin nipped the bonny babe,Quhile hich the red blude springs."O gentil Nourice! please my babe,O please him wi the keys!""It'll no be pleased, gay lady,Gin I'd sit on my knees.""Gude gentle Nourice, please my babe,O please him wi a knife!""He winnae be pleased, mistress mine,Gin I wad lay down my life.""Sweet Nourice, loud, loud cries my babe,O please him wi the bell!""He winnae be pleased, gay lady,Till ȝe cum down yoursell."And quehen she saw the red, red blude,A loud schrich schriched she."O monster, monster! Spare my child,Quha nevir skaithed thee.O spare! gif in your bludy breastAlbergs not heart of stane!O spare! and ye sall hae of goudQuhat ȝe can carrie hame.""Dame, I want not your goud," he said;"Dame, I want not your see;I hae been wranged by your Lord,Ȝe sall black vengeance drie.Here are nae serfs to guard your hall,Nae trusty speirmen here;They sound the horne in gude greene wode,And chasse the doe and deer.Tho merry sounds the gude grene wode,Wi huntsmen, hounds and horn,Ȝour Lord sall rue, e'er sets your sun,He has done me skaith and scorn."

Interestingly, the version of the music doesn't match well with the oldest lyrics, but makes a better fit to Child's version E:

93E.1 LAMBKIN was as good a mason as ever laid stone; He builded Lord Montgomery’s castle, but payment got none. 93E.2 He builded the castle without and within; But he left an open wake for himself to get in. 93E.3 Lord Montgomery said to his lady, when he went abroad, Take care of Bold Lambkin, for he is in the wood. 93E.4 ‘Gar bolt the gate, nourice, without and within, Leave not the wake open, to let Bold Lambkin in.’ 93E.5 She bolted the gates, without and within, But she left the wake open, to let Bold Lambkin in. 93E.6 ‘Gude morrow, gude morrow,’ says Bold Lambkin then; ‘Gude morrow, gude morrow,’ says the false nurse to him. 93E.7 ‘Where is Lord Montgomery? or where is he gone?’ ‘He is gone up to England, to wait on the king! 93E.8 ‘Where are the servants? and where are they gone?’ ‘They are all up to England, to wait upon him.’ 93E.9 ‘Where is your lady? or where is she gone?’ ‘She is in her bower sitting, and sewing her seam.’ 93E.10 ‘O what shall we do for to make her come down?’ ‘We’ll kill the pretty baby, that’s sleeping so sound.’ 93E.11 Lambkin he rocked, and the false nurse she sung, And she stabbed the babe to the heart with a silver bodkin. 93E.12 ‘O still my babe, nourice, O still him with the pap:’ ‘He’ll no be stilled, madam, for this nor for that.’ 93E.13 ‘O still my babe, nourice, go still him with the keys:’ ‘He’ll no be stilled, madam, let me do what I please.’ 93E.14 ‘O still my babe, nourice, go still him with the bell:’ ‘He’ll no be stilled, madam, till you come down yoursel.’ 93E.15 ‘How can I come down, this cold winter night, When there’s neither coal burning, nor yet candle-light?’ 93E.16 ‘The sark on your back is whiter than the swan; Come down the stair, lady, by the light of your hand.’ 93E.17 The lady she cam down the stair trip for trap; Who so ready as Bold Lambkin to meet her in the dark? 93E.18 ‘Gude morrow, gude morrow,’ said Bold Lambkin then; ‘Gude morrow, gude morrow,’ said the lady to him. 93E.19 ‘O where is Lord Montgomery? or where is he gone?’ ‘O he is up to England, to wait on the king.’ 93E.20 ‘O where are your servants? or where are they gone?’ ‘They are all up to England, to wait upon him. 93E.21 ‘I’ll give you as much gold, Lambkin, as you’ll put in a peck, If you’ll spare my life till my lord comes back.’ 93E.22 ‘Tho you would [give] me as much as I could put in a sack, I would not spare thy life till thy lord comes back.’ 93E.23 Lord Montgomery sate in England, drinking with the king; The buttons flew off his coat, all in a ring. 93E.24 ‘God prosper, God prosper my lady and son! For before I get home they will all be undone.’

(Montgomery is the main piece that doesn't fit in the first verse, but reading Child's collection one sees how the aristocrat's name varies greatly, with two syllable names like Early, Arran, Murray and Wearie being common.)

For some reason the tune reminds me a bit, superficially, of this contemporary tune by Henry Purcell:

The song of Long Lankin usually tells a pretty consistent story: Lankin (or whatever variant of the name) comes to the house of a Lord while he is away, and assisted by a "false nurse" (false in the sense of disloyal) Lankin tortures the Lord's baby, using its cries to lure the Lady of the house downstairs. Some versions of the song cut away at this point, though many include verses to suggest the Lady is murdered with the baby, and that Lankin and the Nurse are punished for their crimes.

Variants include versions of the song (typical of Scotland) where Lankin's motive is provided: he is a mason who was cheated of his pay by the Lord of the house, and so the murders are done out of revenge. There are also versions where other characters, like one or more daughters or additional servants are somehow involved in the crime, usually as innocents who Lankin forces to watch or to reluctantly participate in the crime.

There are some theories as to what the song is about, starting with the name of Lankin. Those who favor the spelling Lambkin tend to say it's a nickname given either to mock him for his quietly bearing the lack of payment, or else that it's an ironic nickname given because of his known violent tendencies. Anne G. Gilchrist in the 1930s wrote about the evolution of the song, and noted that "Lamkin" or "Lammikin" was not necessarily a misspelling of Lambkin, but is a legitimate Flemish name all itself, and might have meant that the murderous mason was supposed to be a foreign workman.

There are some theories, often repeated in spite of the poor evidence for them. One often found in internet results is that Lamkin is supposed to be a leper who is trying to use the blood of the baby to cure his disease. However, the first reason to doubt this is that it seems like Lamkin being a leper looking for blood would be a lot more remarkable than his being a mason or even having no motive at all, and one would thus expect at least some of the surviving versions to have retained this interesting detail. The other reason to doubt it is that there's little evidence baby's blood was ever used as any kind of "folk remedy" for leprosy. (It is mentioned in some high-end medieval medical texts, of a type that commoners wouldn't have access to, and which dealt more with the theory of medicine than its practice. It's more likely some modern academic would be familiar with them, than it would have been for an actual medieval leper to know them.) Finally, the whole notion seems to be based on those versions of the song where Lankin collects the blood in a basin, which is not a consistent element of the story (only Child's F, G, N, O, T, and V versions have the detail -- a relatively small number of the total) and really it seems like it might be included for no better reason than that "basin" makes a rhyme for the necessary -in endings in the song about Lankin, which also seem to provide his motive for using a pin to draw the blood rather than some more efficient weapon if collecting the blood were his real goal.

Another unlikely, but oft repeated, occult-sounding theory, is that the mason needs to consecrate the house with blood in order to finish the job -- though if he went unpaid, it seems odd that he would be so anxious to do so. To explain this, another story that is never mentioned in the song gets added, that Lankin must have killed his own child to consecrate the house and now wants the Lord's child's blood as payback. But this has the same issues as above (no version of the song retains these details which should be more interesting than mere unpaid wages, this ancient practice wasn't used anymore by medieval times much less the 17th century when the song appears, and it's once again all tied to trying to explain the basin versions of the song.)

It seems more likely than any of these supernatural reasons that the song merely retells some known crime, like the songs of Lady Warriston tell of the actual crime which occurred in the year 1600. Between muddied details of the Lamkin songs (for example, the victim is often said to be Lord Weir or Lord Wearie, but also named variously as Lord Arran, Lord Lauriston, Lord Earie, Lord Montgomery, Lord Murray, etc.) and the sad fact that court and criminal records from so long ago don't always survive, it's very unlikely that the source crime could be identified with certainty.

As you can see in the Lady Warriston examples, details of the real crime do get omitted and exaggerated in the folk tradition (the tl;dr is that the real case involved Lady Warriston colluding with her servants to strangle her abusive husband, and the actual murderer was not the Lady herself, but a man named Weir. The songs never mention him at all, and in one version her motive for the murder is not physical abuse but a specific accusation from her husband that he's not the father of her child.) It's an interesting coincidence that Lady Warriston's case is the only old court case I could find that involved a "fause nourrice" (false nurse) who was punished by being burnt at the stake.

As far as a true crime basis for Lankin, there is an interesting incident which happened circa 1575 in Scotland. It shares a few common details -- a revenge crime against a Lord and his Lady, creeping in through an open gate with only the Lady and her female servant discovered at home, trying to lure someone out with another person's scream -- though it is not so exact that one could definitely say it's the same crime. I'm including it for general interest.

The incident was some kind of family squabble gone awry: the trouble began when Lady Hessilheid slapped a servant, Robert Kent, belonging to her relative John Montgomery. Kent, John, and his brother Gabriel Montgomery, returned to her house at Hessilheid (also called Hazelhead) early in the morning to avenge themselves, "and" (I'm translating this out of 16th century Scots for you) "finding the gate of the said place open... [found] the said Lady opening a locked bole, and no person with her and no person therein but one girl, the said Robert Kent pulled her down by the hair of her head backward to the ground, and struck and beat her with his fists and feet numerous many grievously painful strikes wherewith they have bruised and broken her bowels that she is never able to conceive children again... meanwhile Gabriel stood with a cocked pistol in his hand, holding the mouth thereof to the door that comes from the proper chamber of the said Hugh [Lord Hessilheid] to the hall, thinking the said Hugh should have come in at the hall door to relieve his said wife when he heard her cry." The malefactors worried they would rouse others with their commotion before they were able to lure Hugh, and they left, stealing some items and one of his horses when they went. Hugh chased after them but was "met with pistols and drawn swords" and after being badly injured was left for dead.

Evidently Hugh retaliated against his relative Gabriel at a later time, and the Hessilheid servants are later found on trial for his murder.

(And the story didn't end there, as Robert Kent was then acquitted of any wrongdoing, but the Assise later tried for "wilful error" or in other words, rigging the verdict. These court cases evidently went on for a time, back and forth, with no actual convictions of anyone.)

I recently came across a searchable database of English Broadsides (before Youtube, this was how you shared songs, urban legends, gross news and so forth, through broadsides or broadsheets). I began trying to plug in any combinations of words that might lead to early/obscure versions of Lamkin. Some interesting finds:

Contains the phrase "as good a ____ as ever laid stone" as in the older versions of Lankin. Which is odd, because this song is about a miller, who I don't think has a reputation for stone laying? The remainder of the lyrics are about the miller attempting to dupe a woman into sleeping with him in exchange for free flour, but his wife catches on and takes the woman's place in bed.

There is a hint in many versions of Lankin that his real target is some kind of revenge or seduction of the lady of the house, but the connection seems pretty weak beyond perhaps a borrowed line (and perhaps a common tune -- I can't find any version of The Bed's Making.)

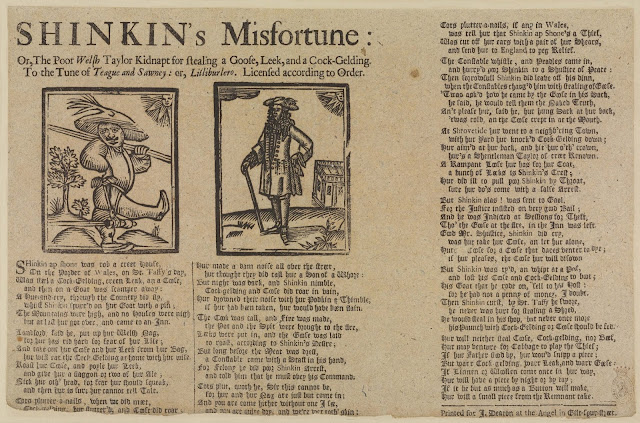

There are several broadside songs about Shinkin, apparently being a stereotype Welsh name. It is superficially similar to Lammikin, Lincoln, Bilankin, and other variants. I actually came across this song because of the lyric "with a pin" -- which here Shinkin uses to spur on a goat. He is a criminal committing crimes, though nothing as severe as murder. Mostly just notable as another similar name circulating in ballad tradition.

This is actually the same story as the old Snow White and the Wicked Queen, but without the hunter feeling a last minute pang of conscience that prevents him from going through with the assigned murder. Then, like the old Greek myth of Philomela, the corpse is baked into a pie that is fed to the father.

The connections to the Lankin story are that the crime takes place while the lord of the house is away hunting; and also the fate of the murderers -- "The cruel step-mother/For to be burnt at stake/Likewise he judged the Master Cook/ In boiling oil to stand." There are also some versions of Lankin in which a daughter of the house is present, and either is killed or, like the scullion boy of this tale, attempts to intervene in the murders.